Written by: Dave Cantrell

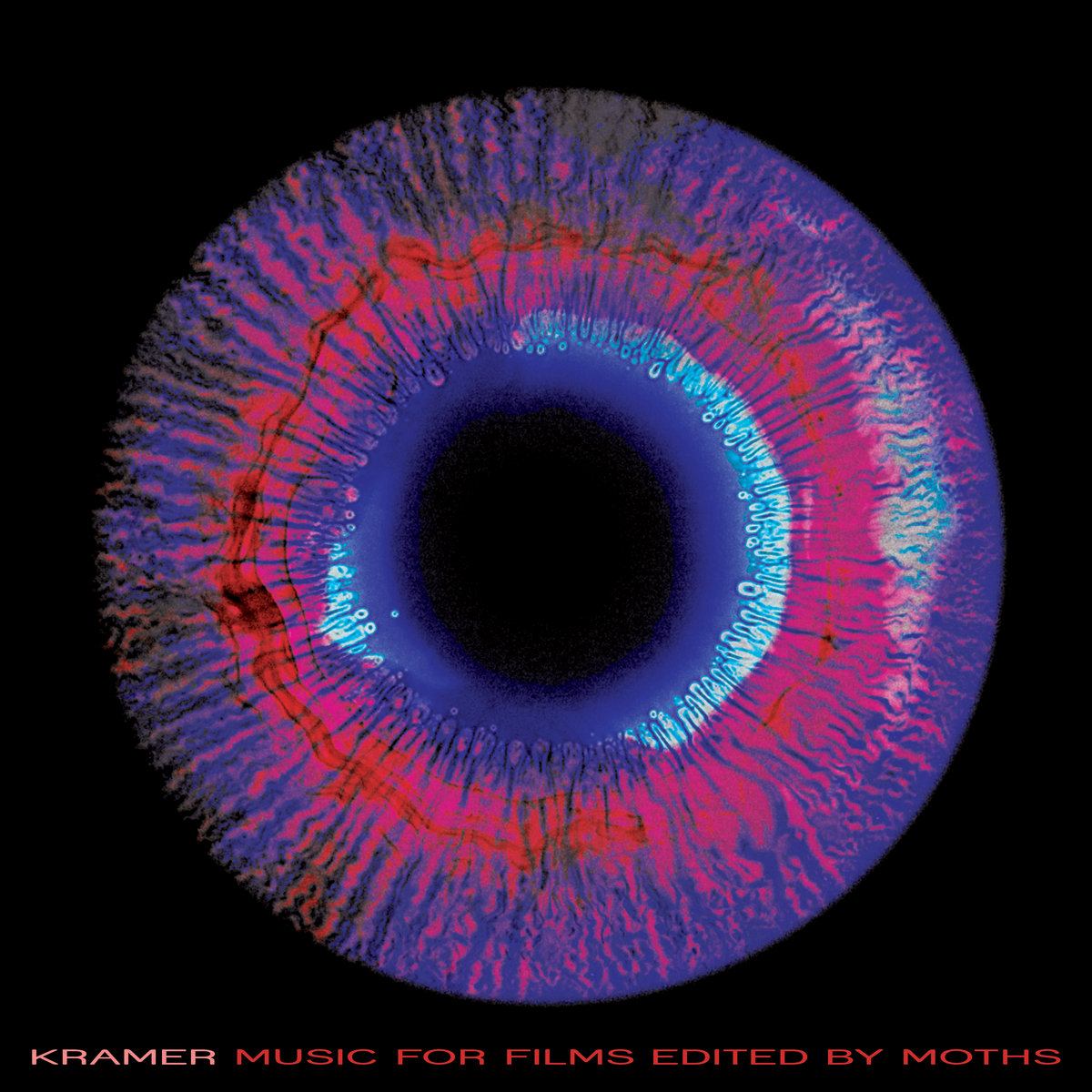

To the extent it has a reputation, ambient music doesn’t in most cases attract superlatives, nor for that matter much reactive heat whatsoever, instead being viewed by that mysteriously droll entity ‘the wider public’ as a passing distraction that, at best, registers on the favorability scale a tick or two this side of muzak. Kramer’s not here to change that – one guesses in fact that, if anything, having hewed for a lifetime toward the variously pop perverse end of the musical spectrum, he’s more likely to relish if not celebrate that fact in some oblique fashion – but being among our most adventurous, respected and avidly restless artists, his immersion in the form, aside from being a somewhat curious departure just by definition, amounts to a trusted invitation to explore a genre that (we feel it’s safe to assume) many if not most of us have pretty much ignored. Because, really, if anything can be said of Kramer’s storied, eccentric career it’s that it’s never been boring and in fact, over the course of nearly four decades, it’s been something of a reliable bellwether, consistently leading us toward a music where the word ‘interesting’, for once, actually means interesting, which is to say challenging, surprising, not infrequently irreverent and always worth our attention. His work on the piquantly-titled Music for Films Edited By Moths is no different.

Whereas the previous couple of tracks we’ve premiered from this album have stuck to the vocals-free ambient standard, “Requiem for Max” departs somewhat from that customary status and for a very compelling reason. Dedicated to the work and memory of the translucently brilliant writer WG Sebald – who preferred to be referred to as Max – the track and video (shot with a quiet, visionary grace by Tinca Veerman) both plumb those privately excavated wells of loss and recollection where each of us store our past in all its tremors of pain and joy. As this also happened to be the focus of Sebald’s work the decision to insert the author’s voice into the mix was pretty much a fait accompli. Echoing in our ears like murmurations of the soul, their appearance only underlines the power of this piece and, by extension, the album entire.

What Kramer seems to have understood – and that this writer has only come to realize – is the extent to which ambient, like any instrumental music, connects to the music our Western culture predominantly produced for centuries, where, excepting oratorios (and opera, a whole different medium), the emotional component, absent a soulful, expressive vocal, was entirely dependent on the swell of violins and the percussive emphasis of timpani and the like. Though subdued in an effort to mesh with the environment rather than appeal to its inhabitants’ baser impulses, this music, paradoxically, is often more powerful in its contemplative sorrows and exultations than Tina Turner at her most glorious. This is not a conclusion those of us raised on the Stones and the Who or whatever complement can arrive at without some resistance but then again when has resistance ever served anyone well in the pursuit of musical exploration (Parliament and the Pistols and Thelonious Monk, as a ‘for instance,’ should all, by our lights, fit comfortably inside any true music fanatic’s collection). Though the phrase as most commonly stated is a slight bit different, we’ll put it this way: Free your mind and your heart will follow.

[pick up your copy of Music for Films Edited By Moths here]