Written by: Don Ciccone

It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that pop music today might be very different if not for a radio repairman from Southern California by the name of Leo Fender. Before Leo, the electric guitar was either a hollow body jazz box, or a thick slab of wood that sat across the player’s lap and was meant for Hawaiian music or Western Swing. Thanks to his truly innovative designs, the company Fender started in 1946 is still going strong and still bears his name.

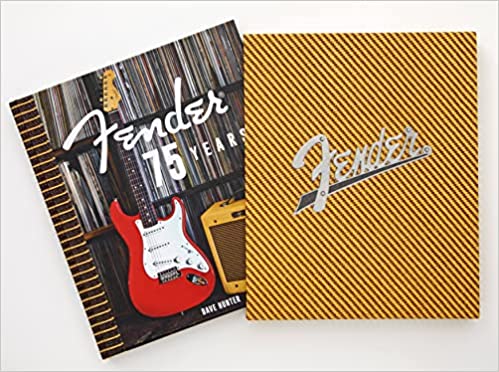

Veteran guitar and amplifier historian, Dave Hunter concisely presents the history of that company’s journey, from its humble beginnings to the present, in a beautifully illustrated hardcover book simply entitled, Fender 75 Years. Mr. Hunter has written some fine books on guitars and amps and is well known to readers of Guitar Player magazine as well as Vintage Guitar. We can think of no one better suited to tell this fascinating story.

He spoke to us by phone from his home in Maine.

Stereo Embers Magazine - You write these great articles about forgotten guitar amps in Vintage Guitar magazine.

Dave Hunter – Thanks. There’s a lot of quirky stuff out there. I don’t think either the editor or I thought it would go on this long, but these amps keep coming out of the woodwork. The quirkier they are the more fun it is, in some ways.

SEM- Does Vintage Guitar find these oddball amps for you, or do you find them?

DH – I find them. Generally, it’s my responsibility what I’m going to write about, but very often — 40 or 50 percent of the time maybe– readers are coming to me, or coming to the magazine, and saying they’ve got this old thing. They’re aware that the column has been going this long. They contact me and say, “I’ve got this old amp, what do you think?” And I’ll take it from there and see if it’s worth writing about. They seem to keep coming and I guess they probably will for the foreseeable future. There are so many oddball amps out there. And then we’ve got the occasional prototype from Fender or Gibson — very early examples. It kind of applies to the Fender book. It was kind of a natural lead on in some ways since I write about that kind of stuff anyway.

SEM – Were you commissioned to write the Fender book or was it your idea?

DH – I was commissioned but, after the starting point, a lot of it was my idea. The initial foundation of the idea was that of the publisher. They noticed it was Fender’s 75th anniversary and said we should do a book on it. And we got Fender involved. It is a licensed, authorized book. It wouldn’t necessarily have to be, but the real benefit of that was to have their participation. As you can tell from the book, they opened up their photo archives. There was a lot of interesting old stuff. That really made it, visually, a lot more interesting than it would have been.

SEM – Besides the great look of the book, it’s very readable. Previous Fender anniversary books were more like reference tomes. But yours is a like a story. Was that your plan?

DH – Yeah, it really was. We had to straddle a fine line, in a sense. There was a strict limit on how many words could go in. A book that has a lot of images has a pretty strict word limit. Every page of text really needs illustrations. We had to straddle this fine line of making it informative and telling the story, while not going over deep into the minutia. I think that worked to the benefit. It forced me to tell the tale and keep it moving along. I tried to touch in depth on the more important innovations but also keep the narrative going so there was a story people could follow and not get too bogged down in what type of tubes they were using here or there. I very intentionally wrote it that way myself, but the editor was very on board with the plan that it could be something that somebody who’s not that deep into gear could read and, hopefully, enjoy. And yet the gear heads could also get something out of it. That was the goal. Hopefully it worked.

SEM – It almost feels as if you’re watching a documentary as you’re reading it.

DH – Thank you. I think it would work well that way. I keep meaning to talk to the editor and see if we could get some tv people interested. It’s still pretty specialized, though.

SEM – The Leo Fender Story really comes through. You could hand this book to someone who doesn’t play guitar.

DH – That was the idea. The thing that always fascinated me is that Leo Fender came up with these basic ideas in the middle of the last century, along with some of the guys he was working with. Between them — sort of upstarts in the industry — and popular music itself, they kind of fed off each other. That really changed the course of the guitar industry. And Fender changed the course of popular music according to what they created. Obviously, there are other companies involved, but I think Fender did that more than most. They kind of re-drew the blueprint for the electric guitar. There was a moment when I was thinking the story’s been told so many times but then it became fun to try to find a new way to tell it, and, as you say, to make it narrative non-fiction and read like a story.

SEM – That must have been tricky because you’re a guy who’s written some very technical stuff. You wrote that book on tube amps that explains what’s inside a guitar amp and how it all works. [The Guitar Amp Handbook]

DH – That’s what we couldn’t do this time. A lot of people have done good books along those lines, so I figured those are out there. Fender didn’t have a heavy hand in the book, but they wanted the history to be fairly well paced and they wanted the newer history to get in there. We couldn’t spend 99 percent of it on the pre-CBS stuff and then sign off with a page that says, “And they’re still making guitars.” And that’s fair since they were investing their resources in it themselves. It was fun trying to find the points that were interesting after the “golden period” and seeing what they did that was significant, decade by decade. One of my concerns was that you’d have some Fender fans, or owners of guitars that, after they got the book, would say, “I like it, but they didn’t talk about my specific — this or that.” Sadly, it couldn’t be a completist thing with something on every single item they ever put out.

SEM – It’s not an encyclopedia. It’s more of the story.

DH – That was the crux of it, that this is an interesting history of a company that came along and really helped to reshape a big part of popular culture. And popular culture, at the same time, informed their work. A perfect example of that would be Leo’s connections with musicians who, in the early days, would try things out and give their feedback.

SEM – Let’s talk a little bit about those early days. The company started in 1946, just after the war. Just as America is beginning to become Number 1 in the world. That parallel is rather interesting, isn’t it?

DH – It really is. The whole West Coast/California scene was still a relatively small scene. There weren’t many guitar stars yet that were household names the way there are today or the way they would become in the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s. And yet it was this feeling of a kind of brave new world. The technology was kind of catching up with what they wanted to do. The tube amps had progressed to where Leo Fender could take basic designs from the tube manufacturers’ handbooks of things you could make, and really work them into high quality products. He ran with that. He probably benefited from coming at this thing from scratch rather than having a legacy like Gibson or Gretsch.

SEM – He came into it from radio, right? Radio repair?

DH – Exactly. He wasn’t coming into it as an instrument maker. He was coming in with a blank slate and seeing what he thought musicians could use to improve their lives and make things easier. Make the sound they wanted to make. The idea was to get the guitar players out from the back of the stage and get them up front. He benefited from that fresh perspective and not having any baggage.

SEM – If you’re going to criticize Fender guitars, let’s say, compared to Gretsch and Gibson guitars, you could say Fenders are just bolted together, etc. But, when it comes to amplifiers, if you look at those old Gibson and Gretsch amplifiers, there’s no comparison with Fender amps of the day. Why is that? Why were they so loud, for one thing?

DH – I think he just identified the needs that professionals had. It’s hard to say without speculating, but it might be that it was pre-rock n’ roll. It was Western Swing and Country players that Leo was dealing with. He saw what was out there for them and said, “I’m just going to make it better.” In terms of sounds, he was always striving for clean and bright. Obviously, he wasn’t looking for the overdrive. His designs just happened to suit the new popular music that was coming better than the old stuff did. He didn’t hit the ground trying to feed the jazz market like the other guys were still kind of stuck in. Leo’s sound was rooted in Hawaiian music, essentially, which segued over to Western Swing and the lap steel guitar. That was the first electric guitar music really, the Hawaiian stuff. He had that sound identified before he started building guitars, and he made amps that would accentuate that.

I think it was the combination of that and being determined to make them roadworthy and serviceable and just seeing what the pros needed. But you’re right, you look at a Fender amp from even the mid-fifties and you look at a Valco or a Gibson or any of these others… Gibsons are pretty good, but they’re still not put together nearly as ruggedly. And the circuits aren’t laid out as cleanly.

SEM – One surprising thing about the early days was that Leo and his partner Doc Kauffman apparently invented the record changer.

DH – Yeah, isn’t that funny? You don’t hear much about that. I don’t know if others preceded them or not but they got a patent on it so it must have been significant. It must have been a first of some sort. I forget what they sold it for, enough to give them seed money, but inconsequential as far as how big that must have become as an invention.

SEM – It also goes to show that Leo was coming at it from a hi-fi point of view.

DH – Yeah, true. Exactly. That was his thing. He was into radios and record players. Local musicians noticed that if he could build radios, he could probably build them an amplifier and it kind of went from there.

SEM – You mentioned lap steel guitars. In the book, you show how the pickup in the first Fender lap steel is very much like what shows up in the Telecaster. But it’s not just the pickup, is it? The shape of the Tele, a thick slab of wood that could sit on your lap, is not that different from a lap steel. It’s essentially a lap steel with a long neck.

DH – Yeah, it’s true. It’s a lot closer, just being a big slab of wood. And the whole solid body concept. There were various other people who did dabble in solid body guitars before Leo Fender. Bigsby and so forth. But they were never widely produced or anything. Otherwise, the first solid bodies were lap steels that all the big companies were making by that point because that was a popular market. I think Fender had the advantage of seeing that the way forward was to translate that sound into a Spanish electric guitar rather than trying to kind of reverse-engineer the hollow body jazz box.

SEM – Were they also thinking of cutting costs by taking this almost…Henry Ford…approach?

DH – Definitely. Even though it was revolutionary, they brought it out at a price that was much less than the nicer Gibson archtops and stuff like that. But it wasn’t cheap for the day. The first Telecasters were two hundred and something dollars. $225 or something, which is a lot of money in 1950, but still less than the bigger, more elaborate Gibsons. That was certainly the idea. Everything could be bolted together. That was a radical concept. If you wanted this bright clear sound that the pickup was going to be the chief component of, then you just wanted a solid guitar, and it didn’t matter if you bolted the neck on and all the hardware was bolted on and stamped from metal and stuff. It was going to make the sound you wanted, regardless. Which is kinda cool and which always fascinates me. He didn’t just start making electric guitars and do a version of what was out there. He didn’t look at guitars that existed and make them electric. He completely redrew the blueprint. Which is pretty cool.

SEM – Like a whole new invention.

DM – Entirely, yeah.

SEM- There was a funny story in the book about termites eating the lap steel guitars.

DH – That’s one of the stories that’s difficult to pin down. That’s apparently what it was. They sent some lap steels out to the dealers, and they all got sent back– like a hundred of ’em– and they put them on the bonfire out back, or something like that. They seem to have gotten funky wood from a supplier. That was very early on. Before the Telecaster.

SEM – You mention women working at the factory. Were they there pretty much early on?

DH – Yeah, definitely. Seems like, near the very start of Leo having any employees, he was employing women in the assembly and manufacturing. There obviously aren’t many people around anymore to talk about that of course, but by all accounts, Leo treated people well and was a good employer. He hired women and valued their work. Of course, there were women in a lot of types of manufacturing during the war.

SEM – Women must have been wiring Gibson pickups as well, no?

DH – You would think so, but you don’t hear as much about that. The Fender thing is that you have the initials underneath. Some of the pickups were signed, or some of the cavities were signed, with a name. Or the amp, at least in the tweed years, had a little piece of masking tape with a signature. “Lupe” or “Lily” or somebody. One of the women, and I believe she’s quoted in the book, spoke to us through her grandson and she related the message that Leo was friendly and welcoming and didn’t talk down to them or anything and that she really enjoyed working there.

SEM – The Telecaster really seemed to go over right away with country players, didn’t it?

DH – For sure. That was largely because those were the people he was working with and addressing.

SEM -Western Swing players?

DH – Exactly. He was hanging out with those guys and going to those venues and seeing them perform. That was the market he was feeding from the start, like you said, having that guitar evolve out of the lap steel guitar, from Hawaiian to Western Swing. Those Western Swing players were saying, “Well these Hawaiian style guys have a great, clear and articulate sounding lap steel. We need something for ourselves.”

SEM – The early Telecasters, Broadcasters and Esquires were obviously shipped with heavy gauge strings. Were they also flat wound?

DH – They were. My understanding is that they mostly were, in the early days. Round wound strings really weren’t much in existence until later into the 1960’s and so forth.

SEM – You can really hear that on Johnny Burnette’s records. You show his group in the book. If you put heavy flat wounds on a Telecaster, you instantly get that Johnny Burnette sound.

DH – Definitely. That’s a good point. It’s one of the reasons some of the guitarists from that era will sound different. Round wounds are so much brighter. People say the same thing about Rickenbacker guitars. Beatle fans buy them just as hobbyists and they want to get that Beatles sound, but the word is you really can’t get it unless you put flat wounds on them.

SEM -You’ll sound more like the Beatles if you put flat wound strings on a Strat, than if you put round wounds on a Rickenbacker or a Gretsch.

DH – Yeah, exactly. When Fender was reissuing the Jaguars, there was a bit of stink that they didn’t sound quite right and that was because the originals came with flat wounds.

SEM – In the original brochure where Fender was announcing the Jazzmaster, you could clearly see the strings were flat wound.

DH – And a lot heavier.

SEM – It’s the same with Buddy Holly. Heavy flat wound strings on a Fender Stratocaster. The Crickets were on The Ed Sullivan Show and Buddy had the Strat. Did that appearance put the Strat on the map, would you say?

DH – He was probably one of the first popular artists that did. We think of the Strat now as a rock guitar. Rock and blues. But again, Leo was building for the country artists, really. Buddy Holly was one of the first really popular artists to play a Strat, unless I’m forgetting somebody. One of the guitarists in Gene Vincent’s band, the Blue Caps, played a Strat also. But he wouldn’t have been as widely known as Buddy Holly.

SEM – In the same chapter with the Stratocaster, you talk about the first Fender bass. You mention that it was called “the Fender bass.” Legendary session player, Carole Kaye played a Fender Precision, but she said, “We just called it ‘Fender bass’.” It was a new invention, wasn’t it? As opposed to an upright bass or the Dan Electro 6 string bass, all of which were standard instruments, often used together, in the studio.

DH – Right. A lot of session people used the Dano 6-string bass as well. I remember so often looking at credits and you’d see so and so, and it would say, “Fender bass.” That really highlights that. “Are you gonna play bass or are you gonna play the Fender bass?”

SEM – “Bass” meant upright bass.

DH – Exactly. This was the introduction of the bass guitar as opposed to being bass proper. A lot of people say that Leo’s creation of that bass had the biggest effect on popular music of anything he did. Which is hard to imagine, but talking about those terms, you can see how that might be true.

SEM – And when Fender got around to making a 6-string bass, they put a vibrato bar on it.

DH – Right. I can’t imagine that staying in tune for very long.

SEM – Speaking of vibrato, the vibrato system in the Strat, with all those springs, was totally revolutionary, wasn’t it?

DH – Yes, definitely. We’re so used to seeing that thing now but when you pause to look at it and clear your mind, it is a real contraption. And the fact, for all that, it works so well. I mean if you don’t know how to set it up, you’ll be out of tune all the time, but if you set it up well, it will stay in tune pretty well. If you look at the vibratos that other people were doing, not many were putting good ones on back then. The ones that came out soon after from all the copyists were real junk, by and large, compared to the engineering that went into that thing. It’s interesting, as the book discusses, that their intention was not to come out with that vibrato on the Strat. They had some real problems with the one they were trying to do which was kind of like an early version of what ended up on the Jazzmaster. They couldn’t quite get it right, so they devised that steel block in the back to make up for the mass that was lost by having it kind of floating on the springs and so forth.

SEM – And then you had guys like Hank Marvin, of the Shadows, who just rode the thing.

DH – Yeah, exactly. It became their whole style. Which would have been difficult to achieve on anything else. The Bigsby was around and people like those. They have their feel and everything. But you certainly can’t do some of the things you can do on a Strat vibrato.

SEM- A problem some players have with Strats is that their hand always seems to run into the volume knob.

DH- I know. A lot of people swear by it because they can roll it up with their pinky finger. But I know what you mean. I do the same thing. I kind of got used to it, eventually. I was always more of a Telecaster player than a Strat player for that reason, probably. The knob always kind of got in the way.

SEM- Getting back to the book, from there you go on to the amps…. the tweed era. The slipcase of the book has a nice tweed design.

DH – They did a good job with that. It was pretty dramatic. It was fun to see that when my copy came. I didn’t know that was going to be happening.

SEM- After tweed came the brown amps, and then the blackface era. There really is a difference in sound between each, isn’t there?

DH – Definitely. They were evolving rapidly, too. The book doesn’t give you much minutia, but in that section and in a later section you see how they were changing up circuits within the same year. They would come out with something and then they would have an idea to make it better and they’d just go ahead and change it up. They wouldn’t make a big fuss about it and change the model, but they might stick an “A” or a “B” on the end of the number or something. Like with the Bassman. There was the 5F6 and the 5F6A.

Leo was striving toward a bigger, clearer sound and the tweed amps do a good job of that, compared to what else was around. He was always striving for more clarity, more power and more headroom. The circuits kept evolving in that way. People often talk of the brown amps as being halfway between the black and the tweed, but they’re really much closer to the black amps, circuit-wise. He kind of radically changed how the pre-amp circuit works, which evolved into that more scooped, more clear sound. They were putting a lot of thought in there.

Gibson put out a lot of interesting models and they had some good engineers, but a lot of the amp makers of the day seemed to treat the amp as a by-product. They had to have some amps that people could plug guitars into. ”Maybe they’ll buy our amp when they buy our guitar.” That type of thing. Fender amps, as you know, were very often being used by people who played many other makes of guitars, just because, for most people, they were the best amps you could get.

SEM – You’ve been quoted as advising people to go into a music shop and plug the most expensive guitar into the cheapest amp there and then plug the cheapest guitar into the most expensive amp in the shop. The result is that you find out it’s the amp that shapes your sound.

DH – Exactly. That’s a quick way of seeing the difference that that makes. Between the fifties and the early to mid-sixties, the Fender team brought in an incredible amount of progress into amp design. Of course, a lot of people came to appreciate that the tweed amps were great for something else: Cranked up for rock n’ roll and having that mid-rangey gritty, grindy sound. But Leo didn’t like the amps distorting. All reports say that he didn’t really like the sound that became the rock n’ roll sound with heavy distortion and stuff. He wanted the clean thing. Well, it was rooted in what the country and western swing players were looking for.

SEM – Some players say Fender amps give you the true sound of the guitar.

DH – Interesting.

SEM – If you compare them to Vox, Vox is a sound.

DH – That’s true. Marshall also is a sound. That sound can be great if you’re looking for it, but it is tending to corrupt the sound of the guitar signal a little bit more. It’s interesting because they would have been developed with some of the same goals in mind, way back when, before people were looking for the distortion. Except for Marshall, because they were kind of competing for the Rock crowd from the start. But, yeah, Fender was always striving for clarity and that sweetness. Different goal, and obviously they were very successful with it.

SEM – Let’s talk about the addition of reverb in Fender amps. That’s another big innovation. Vox, for instance, didn’t have reverb in their amps. And the Fender reverb was just incredible.

DH – They weren’t the first to put reverb in. Ampeg, I think, had it and theirs was pretty good. Maybe Premier and some of the smaller makers also had it. Danelectro or Silvertone, maybe. Other than Ampeg, though– the ones that did have reverb early on– it was pretty junky sounding. It wasn’t really anything to write home about. It was a pretty cheap, metallic, spanky sort of thing. Fender’s was really lush. Thick and rich sounding. It made a big difference.

SEM – Was that because they used a longer spring?

DH – That was part of it and just the more complicated circuit. They put the effort in with a circuit that requires two pre-amp tubes and just a lot more going on. Plus, the lavish spring pan. All that feeds into a better-quality sound.

SEM – The sound of the separate Fender Reverb unit is a little different compared with the reverb built into the combo amps. It’s the sound you hear on those early surf records, isn’t it?

DH – Yeah, that’s it. They were making it sort of the same way, but it forces you to put it in front of the amp rather than down the signal change, and that changes the way it sounds.

SEM – In 1965, CBS came in and bought the company and things were okay for a while but then you quote Don Randall, who was there from the beginning, saying “things got stupid.” He said they weren’t using the old manufacturing equipment.

DH – Yeah, it sounds like they initially went with the designs and the work that people had been doing for a while but then, being a big corporation, they figured they’d better stick their hand in. Executives started messing with things. Obviously, they were looking at the bottom line, but they made the same old mistake. If you start screwing up the product, then the bottom line’s going to suffer anyway in the effort to make it cheaper and crank out more stuff. The product shouldn’t have changed that much except the guitar had become so popular and they were cranking out so many guitars and amps and related products– trying to feed this monster of a market– that they were just cutting corners. As Don Randall pointed out, they were really not making use of the knowledge that they had there and the legacy of knowing how to do these things.

SEM- Twenty years later, CBS sold the company to a group of managers. Soon after, supposedly, good Fender guitars started coming out of Japan, is that right?

DH – They went through this transitional period. The people that ultimately bought it with the management buyout essentially went in pretty quickly, making the effort to do it right, but when they purchased it, they didn’t get the factory in the deal. So, for a while they had to get things made in Japan to kind of tide them over for a few months, or the best part of a year, maybe. They had submitted good designs. The Japanese factory was making good quality stuff and a lot of people feel it was better than the last of the US made stuff before that period. That kind of opened the door to the reissue series and the split between the reissues and the newer designs and things that people enjoy today. The reissue became an obvious thing. If everyone is saying your guitars were good up until such and such point — 1965 is the year for the most part — it makes sense to just go back and make ’em like that again.

SEM – There was this guy you mention in the book who was doing that himself, Vince Cunetto.

DH – Yes, Vince Cunetto. When they opened the Custom Shop, eventually, and wanted to make the aged – what they call the “Relic” series — they wanted to do those.

SEM – But he was already doing it on his own, right? I mean, basically, he was almost like a forger.

DH – He was, essentially. He wasn’t intentionally working as a forger, but he was fascinated with recreating the old stuff. Initially, he was just recreating aged parts and things people could use to bring their old guitar up to scratch. Or make the guitar look right. But then he started putting together complete guitars. He happened to meet Jay Black who was one of the early guys at The Fender Custom Shop. Jay Black said, “You know you obviously can’t keep doing this. Come and work for us. We can use an accurately aged series of guitars like this.” So that was the story of the Relics.

SEM – But it’s not just the aging, is it? Custom Shop Fenders seem to be light weight and they really resonate.

DH – You’re entirely right. It’s not just the look of the aging. They continue to improve. The Custom Shop has made great guitars since its inception, to be fair, but they continue to get better and better. They more accurately recreate the vintage guitars regardless of what the finish looks like and the aging. That’s the thing that’s worth noting. With the Custom Shop’s series of guitars, you’re getting Fender’s best made recreations in the first place, and then if you like them to look aged and be appropriate to when they would have been made, then that sort of goes on top.

SEM – Are they using different wood in the Custom Shop?

DH -They’re using more select wood, yes. Generally, the cream of the crop from what’s available because people are expecting more. They do tend to be lighter and just be more desirable, sonically, because people are paying more for that. And people working in the Custom Shop tend to be more skilled as individual craftspeople.

SEM – Is the Fender Custom Shop using different types of wood, like ash vs whatever, or is it the age of the wood that’s different?

DH – Custom Shop is still considered a big manufacturer so they’ve gotta buy a lot of wood, but it tends to be higher quality, which tends to mean better aging, better drying out — things like that. They’re getting wood, if it’s ash or alder, that’s appropriate for the model of the guitar they’re making. Or the era, whether it’s a mid-50’s Strat or an early 60’s Strat.

SEM – A Custom Shop early 60’s Strat seems to vibrate through your body as you strum it, even unplugged.

DH – That’s the impressive thing. I can totally see how you would get that feeling. I think guitarists just got used to these things being so heavy and dead for a while. That’s why, in the 70’s and 80’s, the move went to all those high output replacement pickups and stuff like that to try and get some life out of them. But you get a good old guitar that resonates well, and it’s got fairly low output pickups and you realize how lively it is and how dynamic and how much tone is going on. Fender’s done a great job of recreating that legacy and recapturing that stuff. And just making that available, since the originals are really out of reach for most of us.

SEM – And that’s still going on, The Custom Shop?

DH – Yeah, they’re still doing that. Even more so. They’re making even more high-end guitars like the one-off instruments they make. Master Builder and stuff like that. They’ve done a great job of recapturing that.

SEM- That brings us up to today. What do you think of this latest, Acoustasonic, series?

DH – It seems to have grabbed people. I never had a need for a guitar that doubled between acoustic and electric, so I was never drawn to such a thing, but they seem to be really popular.

SEM – Do you remember the old Fender acoustic guitars? They didn’t have the greatest sound but what electric guitar players loved about them was that they felt like electrics. They seemed to have the same neck as Fender electrics.

DH – Right, they had that Fender neck shape, and they were easier to play. Exactly. The idea was: We’re gonna make an acoustic with a bolt on neck that’s a Fender neck.

SEM – If only they would do that again.

DH – That would be a good idea.

SEM – Well, in any case, we can certainly say, “And they’re still making guitars.” 75 years later! Thanks for the inside story on your excellent book.

DH – My pleasure. Thanks for your interest.