Written by: Matt Fogelson

For more of Matt’s work, check out his official site:

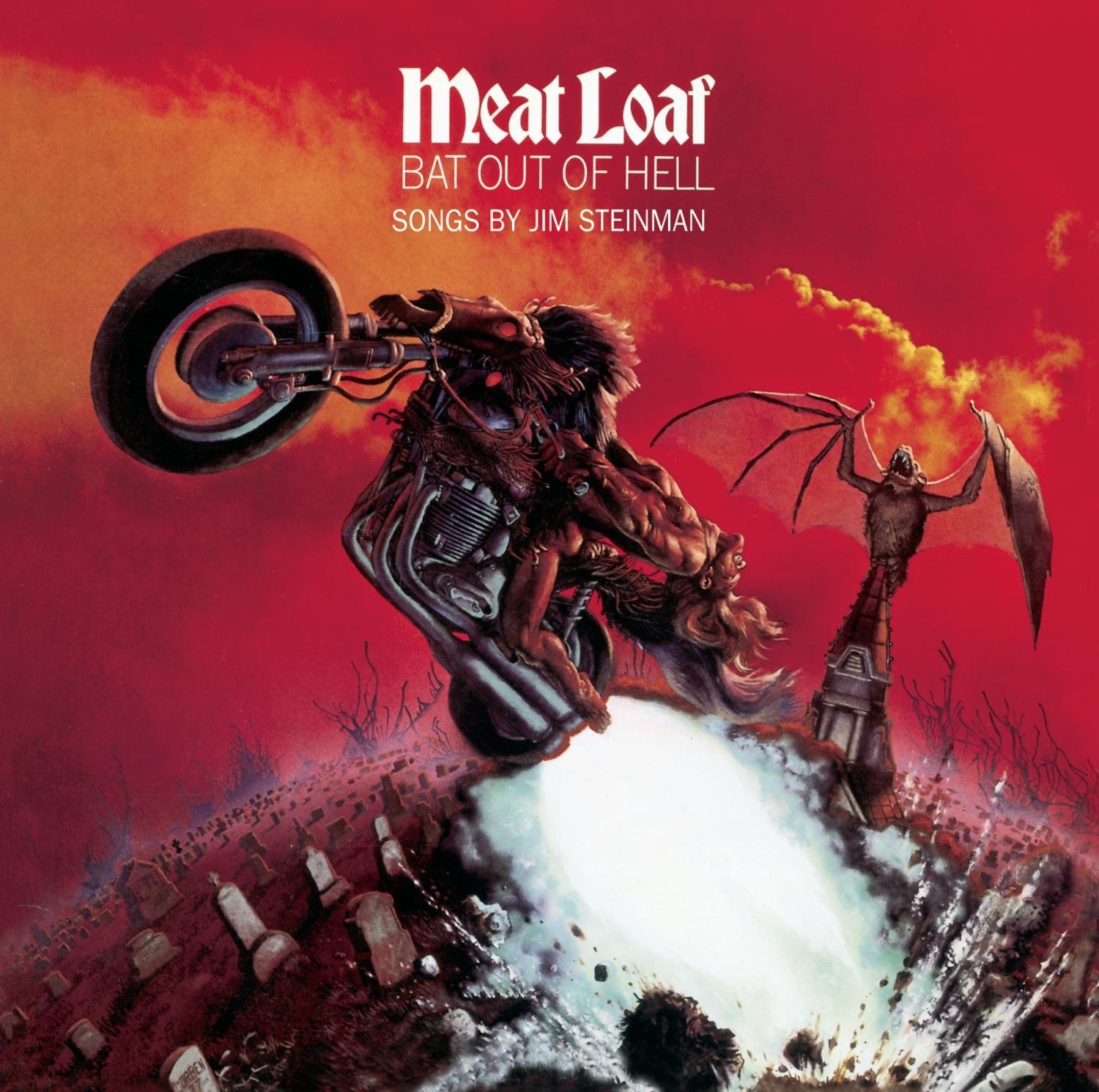

Of life’s great mysteries, surely among the most impenetrable is how Bat Out of Hell, Meat Loaf’s adolescent wet dream of an album that was released forty years ago today [October 21, 1977], came to be one of the best-selling albums in the history of the record industry, cracking the top five in some rankings, and out-selling nearly all the pillars of the rock canon.

I pose the question not out of cultural disdain from atop a critic’s ivory tower. On the contrary (and in the spirit of full disclosure), I adore Bat Out of Hell. It is like a treasured family heirloom I have carried with me through every life stage. My love of Bat Out of Hell borders on the unnatural. I own Bat Out of Hell in four different formats. I have watched documentaries on the making of Bat Out of Hell. I have even read Meat’s autobiography, To Hell and Back. And I am left wanting more helpings of Meat Loaf.

No, I pose the question because notwithstanding my own bro-mance with the record, I have trouble understanding how a record like Bat Out of Hell could become so wildly popular. Very few people consider Bat Out of Hell a “serious” rock record. That includes the record’s producer and serious rock star in his own right, Todd Rundgren, who reportedly rolled on the floor laughing when he first heard the songs. Kasim Sultan, who played bass on the record, had a similar reaction, recalling in a 2013 interview that “through the whole process I remember distinctly saying to myself, ‘This is just the biggest joke that I’ve ever been involved in. I cannot believe that these people got a record deal! This is just crazy. I’ll never hear this record. It’s just a joke. It’s a comedy record.’”

One can understand Sultan’s and Rundgren’s reactions.

The songs, all of which offer a slightly different riff on the theme of juvenile sexual angst, are completely over the top, both lyrically and stylistically. The lyrics to “Paradise by the Dashboard Light,” one of the album’s most iconic tracks, leave little to the imagination, presaging Spinal Tap’s “Lick My Love Pump,” but without the irony: “So open up your eyes, I got a big surprise/It’ll feel all right, well I want to make your motor run.” The interjection of long-time New York Yankees announcer, Phil Rizzuto, to provide a metaphoric play-by-play of the coupling (“There’s a line shot up the middle, look at him go/This boy can really fly!/He’s rounding first and really turning it on now, he’s not letting up at all/He’s gonna try for second!”) while the participants pant and groan in the background, is absurdist. As is the opening spoken-word dialogue to “You Took the Words Right Out of My Mouth (Hot Summer Night)” during which a woman is inexplicably asked by a man whether she would offer her throat “to the wolf with the red roses,” and then proceeds to question the man about what the wolf will do for her in return (“will he offer me his hunger?”) before finally answering that, yes, she would offer up her throat to the wolf with the red roses. Huh?

The Phil Rizzuto interlude in “Paradise by the Dashboard Light,” it turns out, is one of the album’s more subtle rhetorical devices. Most of the rest of the record is more direct in chronicling the protagonist’s sexual fantasies. In “All Revved Up With No Place To Go”, for example, Meat Loaf describes a recurring dream thusly: “In the middle of a steaming night I’m tossing in my sleep/And in the middle of a red-eyed dream I see you coming, coming on to give it to me.”

In light of the subject matter, and camp style in which it is delivered, one might be forgiven for regarding Bat Out of Hell with a certain lack of seriousness. That was certainly the tack taken by the Dean of rock criticism, Robert Christgau, who in 1978 described Bat Out of Hell as “grotesquely grandiose” and dismissively proclaimed, “Here’s where the pimple comes to a head – if this isn’t adolescent angst in its death throes, then Buddy Holly lived his sweet, unselfconscious life in vain. . . . Occasionally it seems that horrified, contemptuous laughter is exactly the reaction this production team intends, and it’s even possible that two percent of the audience will get the joke.”

The joke, it appears, is on Christgau – 43 million people around the world have bought Bat Out of Hell over the years. By some rankings, Bat Out of Hell is the fifth best-selling album of all time. Seriously? How is that possible? How could Bat Out of Hell out-sell nearly every classic record in the rock oeuvre? More than Sgt. Pepper’s? More than Born to Run? Even if you reject those particular surveys as absurd on their face, and go with other seemingly more plausible surveys, Bat Out of Hell is still in the top 35 all-time, out-ranking countless classic rock staples like the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street and Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited.

The popularity of Bat Out of Hell is truly puzzling. It surfaced out of nowhere in 1977, as if inadvertently dropped by a UFO, with no connection to anything happening in the music world at the time. The album was released a few months after the Clash’s first record helped usher in punk, but Bat Out of Hell is to The Clash as Green Eggs and Ham is to Das Kapital.

Punk is straight-forward, clipped and snarlingly jaded. Bat Out of Hell is grand, operatic, and naive. Punk’s overt political invectiveness helped create a new art form. Bat Out of Hell’s overtly libidinous lyrics did not acknowledge the world beyond the self, with “self” defined narrowly as a male adolescent below the waist. While it took the Clash only 1:56 to convey in “White Riot” the crippling powerlessness of the working class and to call for violent revolution, it took Meat Loaf 8:28 to convey in “Paradise by the Dashboard Light” the fullness of his sexual frustration. The only potential commonality between Meat Loaf and punk is anger: the Clash and Sex Pistols were angry about the political system; Meat Loaf was angry about not getting laid.

If Bat Out of Hell had no connection to the punk scene sweeping rock ‘n’ roll at the time of its release, neither did it share any musical fibers with disco which was then dominating the pop scene. The Bee Gees’ Saturday Night Fever was also released in 1977 and it would be difficult to conjure a more perfect foil to the soave, exquisitely-coiffed Andy Gibb than the hulking, sweating, obese Meat Loaf. When in “For Crying Out Loud,” Meat Loaf asks “Can’t you see my faded Levi’s bursting apart?” the answer is a definitive “yes.”

Perhaps because Bat Out of Hell was so out of step musically, nearly every major record label in the United States rejected it. As Meat puts it in his autobiography, record executives “didn’t just dislike it, they were incensed by it.” (Emphasis by Meat). One of those incensed was the legendary music executive Clive Davis who, Meat recalls, turned to him and songwriter Jim Steinman incredulous, asking, “What are you two doing?” Davis particularly savaged Steinman. “Do you know how to write a song?” he thundered at him. “Do you know anything about writing? Have you ever heard any rock-and-roll music? . . . . You should go downstairs when you leave here, go to Colony Records, and buy some rock-and-roll records.”

Davis’ tirade stands in stark contrast to the “warm welcome” Bruce Springsteen recalls of his first encounter with Davis. In his 2016 autobiography, Born to Run, Springsteen writes that after playing him a few songs, Davis invited Springsteen to join the Columbia records family “with gentle fanfare.” There was nothing “gentle” about Davis’ interaction with the Bat Out of Hell team.

Maybe part of the reason record executives were incensed by Bat Out of Hell was because Meat and Steinman would perform the record live in the executives’ offices and when it came time for “Paradise By The Dashboard Light,” Meat and backup singer Ellen Foley would act out the song’s sexually-charged storyline on the executives’ desks. As Meat describes it, the two would “start making out in the office with Steinman doing the [Phil Rizzuto] play-by-play. We’d just start making out like crazy. It made people uneasy,” Meat recounts in what is likely significant understatement. “These record company guys would be sitting there openmouthed. Aghast.”

Watching Meat’s obese form sweating, screaming and gyrating all over MTV induced physical discomfort in the viewer, so one can only imagine the reaction up close and personal in the executives’ offices (although Christgau would likely posit that sales of Bat Out of Hell were buoyed by viewers’ inability to look away from the train wreck that was Meat Loaf).

Eventually, a minor label, Cleveland International Records, picked up the album. Meat’s manager at the time had worked for Springsteen’s E Street Band and got the record in front of Springsteen’s guitarist, Steve Van Zandt. Little Steven called up the top executive at Cleveland International, and, according to Meat, told him “the little fifteen-second interval at the beginning of ‘You Took the Words Right Out of My Mouth’ was the best intro in the history of pop music,” thereby convincing the executive that Bat Out of Hell was going to be a hit.

Little Steven was indeed prescient. Beyond the sheer number of albums sold, what is so remarkable about the album’s commercial success is the consistent trajectory of those sales over time. Bat Out of Hell remained on the charts in the U.K. for 474 weeks – that’s over nine years. In May, 1991, more than thirteen years after its release, Bat Out of Hell still charted at number 36 on the first SoundScan chart. And forty years after its initial release, the record by some estimates still sells nearly 200,000 copies a year.

How is that possible? I can’t recall the last time I heard one of its songs on the radio. Which is not surprising given the record did not generate a chart-topping single in the United States. “Two Out Of Three Ain’t Bad” was the only song to crack the Billboard Top 20, at number 11. There is certainly no “Stairway to Heaven”-type track still getting thousands of plays a day all over the world.

Nor is there a commercial tie-in to a blockbuster movie, as is the case with some other top-selling albums, including Grease, the Bee Gees’ Saturday Night Fever, Whitney Houston’s The Bodyguard, and Celine Dion’s Let’s Talk About Love (which includes the single “My Heart Will Go On” from Titanic). It’s true a musical version of Bat Out of Hell opened in London this past June to generally positive reviews with The Guardian observing “the best musicals have a compelling storyline, thrilling stage pictures and astonishing sounds. This show completely lacks the first, but. . . two out of three ain’t bad.” The Times of London awarded the production four stars, in part because the play “could have gone oh so wrong,” with actual bats flying around the theater, yet somehow did not. But of course this recent renewed visibility cannot explain past sales.

Nor are there any mainstream covers of Bat Out of Hell tunes to mark its influence and to keep the record alive for new audiences in the way, for example, R.E.M.’s covers of the Velvet Underground prompted a re-exploration of VU in the 1980s. On the contrary, the album has inspired some truly bizarre re-makes, including a Gregorian chant of “Heaven Can Wait” by the German band Gregorian, and an unnerving electronica cover of “Two Out Of Three Ain’t Bad” by Olivia Newton-John for the movie A Few Best Men, an Australian version of The Hangover that one critic called “as funny as a funeral.” If anything, these covers likely diminished interest in the originals.

Despite its immense popularity, Bat Out of Hell has had little influence on subsequent artists (other than, perhaps, Spinal Tap). Albums filled with prodigiously long tracks (several of Bat’s clock in at nearly ten minutes) and over-the-top, Broadway-musical qualities have hardly become standards of the rock canon. The only artist that has tried to emulate Bat Out of Hell is Meat Loaf himself, releasing not just Bat Out of Hell II: Back Into Hell in 1993, some sixteen years after the original, but going to the well again nearly thirty years after its release with Bat Out of Hell III: The Monster Is Loose, in 2006. Not many artists have followed this unconventional (if not patently absurd) sequel trail blazed by Meat Loaf. Perhaps it was Meat’s early movie career in The Rocky Horror Picture Show that inspired the sequel concept. If it works for movie franchises like Rush Hour, why not for albums like Bat Out of Hell? That is actually a fair question to ask given Bat Out of Hell II: Back Into Hell has sold over 15 million copies, with the single “I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That)” topping the charts in 28 countries and winning a Grammy for Meat Loaf in 1994.

Although Bat Out of Hell II was a commercial hit, no subsequent Meat Loaf album has enjoyed nearly the same level of success as Bat Out of Hell so as to continue to drive sales. On the contrary, Meat Loaf’s latest release, Braver Than We Are, was named 2016’s worst album by the Australian website News.com. That outlet re-named the album Flat Out of Hell and opined that “Meat Loaf’s vocals sound like Bob Dylan impersonating Cartman from South Park. But with all the fun that may suggest removed.” Rolling Stone decried the album “a Shakespearean act of hubris,” while Entertainment Weekly dismissed the record with reference to government food regulation: “The new Meat Loaf album should come with a warning label: Contains 70% leftovers, 80% ham and lots of cheese.” Ouch.

Of course, just because an album (or a musician) is panned by the critics and not taken seriously by subsequent artists, doesn’t mean it can’t sell. Carl Wilson, in his brilliant case study of Celine Dion, attributes her phenomenal popularity in the face of critics’ outright disgust, in part to Dion’s ability to nurture an aspirational urge in fans. “Her voice is a luxury item,” he writes. “Her voice itself is nouveau riche.” While there may very well be an aspirational element to fandom, it is not self-evident how the concept applies to Meat Loaf. Few fans likely experience Meat Loaf’s voice as engaging with the divine, as Wilson argues Dion’s fans experience her voice. Nor is it clear what other aspects of Meat Loaf’s persona could be understood as aspirational on an international scale.

All of which brings us back to the question posed at the outset: how does an album that, in the words of Rolling Stone, “defied all marketing odds,” still generate six-figure sales year in and year out?

For his part, Meat attributes some of the success of Bat Out of Hell to an initial review in the British rock tabloid, Melody Maker, which called the musicians playing on the record “the worst band in the history of rock ‘n’ roll.” It was right then that sales began to pick up. Meat believes it was because “all the press came out to see the worst band ever, and ended up spreading the word.” But even if wanting to witness a train wreck, to re-deploy that metaphor, explains some of the record’s initial sales, it does not address the album’s sustained popularity through the decades.

Some critics at the time, inexplicably in my view, compared Bat Out of Hell to Springsteen’s classic, Born To Run, which could account for some of its popular appeal. Rolling Stone named Bat Out of Hell the eighth best Springsteen album not made by Bruce, explaining that “every track sounds like a fever-dream rendition of ‘Thunder Road’ or ‘Jungleland,’” and positing that the album’s success can be attributed in part to fans having “gotten sick of waiting for Darkness on the Edge of Town.”

Really? That seems implausible. Clive Davis certainly saw no similarities between Springsteen and Meat Loaf. True, “Jungleland” clocks in at 9:33, nearly matching the 9:53 length of Bat’s title track, while also approaching the grandiosity of its arrangements. And it is also true that E Street Band members Roy Bittan and Max Weinberg played on Bat Out of Hell, which to some ears may give the records a similar sound. And I suppose lyrically the two albums each speak to a type of escape, although Springsteen was seeking to escape the confines of provincialism in the service of self-fulfillment, while Meat was trying to escape his status as a virgin.

These similarities strike me as superficial and, ultimately, I side with Robert Christgau who, while noting the seeming overlap, saw a clear distinction, admonishing, “Bruce Springsteen, beware – this is what you’ve wrought, and it could happen to you.” To be clear, I too think Springsteen morphing into Meat Loaf would be a tragedy, but only because we would lose the singular greatness of Springsteen, not because Meat Loaf is abhorrent in his own right.

My own theory of Bat Out of Hell’s deep and sustained appeal is in three parts.

First, the record reeks of the self-indulgence of adolescence. To my mind, the popularity of Bat Out of Hell can be reduced to a single anecdote from Meat’s autobiography.

Meat tells us he was prone to concussions as a kid, in part because he played football, but mostly because he was extremely accident prone, being a large and awkward physical specimen. He suffered no less than 17 concussions growing up. Number 11 occurred when he was driving and saw a girl walking down the street “with the largest breasts that you could possibly imagine.” Distracted, he rear-ended the car in front of him and his head smashed against the steering wheel with such force it became lodged in one of the wheel’s openings. Unable to extricate himself, the jaws of life were summoned to cut the wheel to pieces.

That’s Bat Out of Hell. Singularly-focused, ravenous and hyper-dramatic with little regard for consequences. While there are a multitude of rock albums with similar themes of teenage sexual angst, none besides Bat Out of Hell boasts a dramatic flair equal to the drama of adolescence itself. Or as super-fan and commentator, Tim Quirk, expresses it, the album’s “real genius lies in the way it channels the desire of those who have never [had sex], and fear they never will. Bat’s many ostentatious filigrees are . . . a charmingly inept attempt to make its subject matter sound more sophisticated.”

Part Two has to do with the album’s uniqueness – there is still nothing quite like it. Bat Out of Hell is a table for one at the rock ‘n’ roll buffet. It is the Hamilton of rock music, bending the genre nearly past the point of recognition. There’s the absurdly dramatic spoken-word introduction to “You Took the Words Right Out of My Mouth” that Little Steven was so enamored of; the multiple, nearly nine-minute-long tracks; the Phil Rizzuto play-by-play overlaying “Paradise By The Dashboard Light”; the grandiose, Wagnerian orchestration of the title track. It is truly an original. And that still matters.

When Clive Davis kicked Meat and Steinman out of his office, he showed great prescience, telling them they should be on Broadway. “You’re an actor. Actors don’t make records. You’re like Ethel Merman. You’re like Robert Goulet. Ethel Merman and Robert Goulet don’t make rock records. You belong on a Broadway stage.” Other albums – so-called “rock operas” – have been re-purposed for Broadway, most famously the Who’s Tommy. But nobody fails to understand Tommy first and foremost as a rock album. Bat Out of Hell doesn’t fit that mold. It truly is a Broadway musical disguised as a rock album; as such, its appeal is not constrained to the (admittedly large) universe of rock fans. Indeed, it is a fair question to ask whether Bat Out of Hell is a rock ‘n’ roll album at all. Perhaps Clive Davis was right about that.

Third and finally, of course, is the music itself. No album sells 43 million copies unless the music resonates with people and can stand on its own; if the music doesn’t excite, it won’t sell, no matter how unique or tapped into the zeitgeist it may be. But if the music is compelling, coupled with the other dimensions, it can explode. Bat Out of Hell exploded.

Forty years later, the silver-black phantom bike adorning the album’s post-apocalyptic cover, brought to life by the shattering guitar solos ripping through the title track, continues down the road, conquering subsequent generations along the way. So long as teenage boys, all revved up with no place to go, are prone to crashing their cars for ogling large-breasted girls, Bat Out of Hell’s star will continue to shine.

For better or worse, that seems likely.